In an era where energy efficiency and sustainability are paramount, Active Power Factor Correction (PFC) is crucial. Active PFC is a technology embedded in power supplies to optimize energy use, reduce waste, and comply with regulatory standards.

1, Understanding Power Factor: Power Factor (PF) is the ratio of real power to apparent power. Real power performs useful work, while apparent power is the product of voltage and current. A low PF (below 0.9) indicates inefficiency, where excess current circulates without contributing to output. Low PF increases energy losses, strains infrastructure, and may incur penalties from utilities.

2, Types of PFC: there are two types of PFC: passive PFC and active PFC. Passive PFC uses capacitors and inductors to counteract phase shifts in inductive loads. Simple and cost-effective, it’s suited for low-power applications but struggles with dynamic loads and harmonics. While Active PFC employs electronic circuits (e.g., boost converters) to actively shape input current, aligning it with voltage. It achieves near-unity PF (0.95–0.99) and handles varying loads efficiently.

In the following contents, we only discuss active PFC

Active PFC circuits typically use a boost converter topology. Key components include:

- MOSFETs: High-frequency switches regulating current flow.

- Inductors&Capacitors: Store and release energy to smooth waveforms.

- Controller IC: Monitors voltage¤t and adjusts switching to align phases.

Active PFC dynamically adjusts the input current waveform through active control circuits, synchronizing it with the input voltage waveform. This reduces harmonics and reactive power, improving the power factor (typically up to 0.95–0.99).

In today’s electronic world, active PFC usually applies to below applications:

Consumer Electronics: PCs, gaming consoles, and adapters.

Industrial Equipment: Motor drives, CNC machines.

Renewable Energy: Solar inverters, battery storage systems.

Data Centers: UPS and server PSUs enhancing energy resilience.

In active PFC circuit, an indispensable part is inductor. According to previous design experiences, BST share below PFC inductor knowledge.

Active PFC circuits rely on a boost converter to align the input current waveform with the input voltage waveform, achieving a near-unity power factor (PF ≈ 1). The PFC inductor is the energy storage element that enables this process. During the switching cycle (controlled by a MOSFET), the inductor stores energy when the switch is ON. When the switch turns OFF, the inductor releases energy to the output capacitor and load. By modulating the duty cycle of the switch, the inductor ensures the input current follows the sinusoidal voltage waveform, minimizing harmonic distortion. Without the inductor, the circuit cannot smooth the current pulses or maintain the required phase alignment, leading to poor power factor and increased harmonics.

As an engineer from BST once said, one thousand engineers have one thousand ways of designing inductors, the key design parameters for PFC Inductors are usually the same:

1. Inductance Value (L):

The inductance determines how much energy the inductor can store and release during each switching cycle. It is calculated using:

A lower inductance increases current ripple, while higher inductance reduces ripple but increases size and cost.

2. Peak and RMS Current Ratings

Peak Current: The inductor must handle the maximum instantaneous current without saturating the core.

RMS Current: Determines copper losses (I²R) due to resistive heating in the windings.

3. Core Material

Common core materials include:

Ferrite: Low core losses at high frequencies (ideal for 50–500 kHz).

Powdered Iron: Higher saturation flux but greater core losses (suited for lower frequencies).

Amorphous or Nanocrystalline: Ultra-low losses for high-efficiency applications.

Also, BST has an engineering team to design core tooling. Please consult BST for more information.

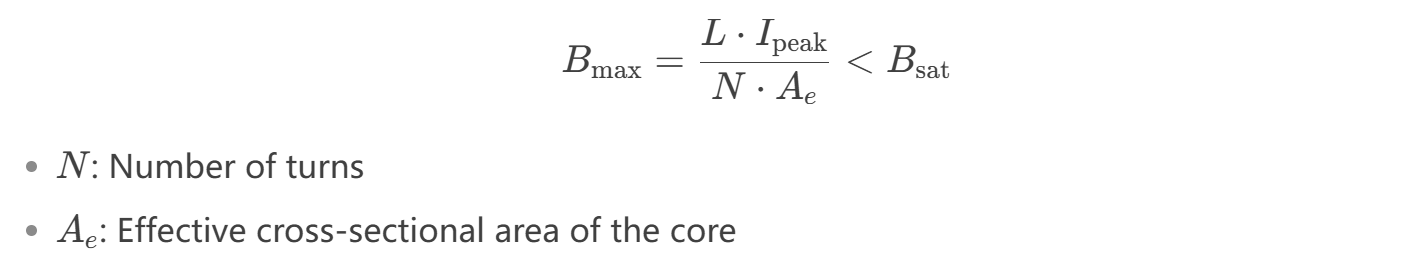

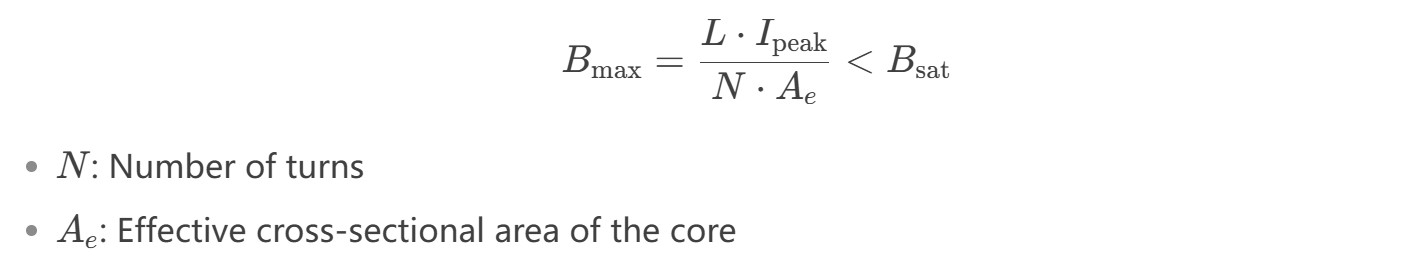

4. Core Saturation

If the magnetic flux density exceeds the core’s saturation limit, the inductance drops sharply, leading to distorted current and potential MOSFET failure. Designers must ensure:

5. Losses

Core Losses: Hysteresis and eddy current losses, which rise with frequency.

Copper Losses: Resistive losses in the windings.

6. Thermal Management

Inductors generate heat due to losses. Proper cooling (e.g., heatsinks, airflow) and core/winding materials with high thermal conductivity are critical to prevent overheating.

Challenges in PFC Inductor Design:

1. Size vs. Performance Trade-off:

Higher inductance reduces ripple but increases physical size. Designers must balance compactness with efficiency.

2. High-Frequency Effects:

At switching frequencies >100 kHz, skin and proximity effects increase AC resistance in windings, raising copper losses. Litz wire or foil windings mitigate this.

3. EMI Concerns:

High di/dt currents can radiate electromagnetic interference (EMI). Shielding or toroidal cores help contain magnetic fields.

4. Cost Constraints:

Premium materials (e.g., nanocrystalline cores) improve efficiency but raise costs.

With more than 10 years design experience, BST is able to conquer these challenges, please contact us for more information.